Courts say no to paper trail, go digital from the top down | Opinion

The National Policy and Action Plan for Implementation of Information and Communication Technology for the Indian judiciary was first put forward in 2005. Its objectives included creation of ICT infrastructure, training of judges and administrative staff and setting up digital archives.

Extending its flagship program for promoting digitisation of government service delivery to Indian courts, PM Narendra Modi launched the Integrated Case Management System (ICMIS) in the presence of Chief Justice JS Khehar couple of months back. The CJI had then promised that the system that would allow litigants and lawyers to file cases using an e-filing portal and allow judges to conduct proceedings without having to sift through stacks of case files would be implemented in the Supreme Court of India after its summer recess.

When the system went 'online' this Monday, the CJI termed it a "happy" moment for Indian judiciary. The esteemed judges of the Supreme Court have also gone on record to term this the most significant reform in Indian judiciary in recent years. But it would only be a happy moment if the tenets of digitization are rigorously applied to this system as they for any other e-governance measure. It would be a reform if it ensures that structural flaws in the system are addressed by embracing ICT.

Till such time, going paperless will only be a measure for increasing administrative efficiency of a system that is almost lagging by a decade when it comes to integrating ICT in its daily affairs. When the ICMIS went live, a number of litigants and lawyers complained of inconvenience as they were not fully aware of the changes being made. While the judges dismissed this as 'teething' problems that will eventually go away, it does make one wonder if they thought if this would be an opportune moment to look at the lessons learnt by the implementation of paperless court at the Hyderabad High Court exactly a year back.

Brief history of digitisation

Since 2005, various governments have tried to push through the e-courts initiative in India, however, none of them put in place the requisite amount of funding and incentives needed to make it successful. The National Policy and Action Plan for Implementation of Information and Communication Technology for the Indian judiciary was first put forward in 2005. Its objectives included creation of ICT infrastructure, training of judges and administrative staff and setting up digital archives. Phase I of this project concluded (after several extensions of deadlines in March 2015) with the successful computerization of a large number of court complexes and judicial service centers down till the district level.

Phase II was approved in August 2015 and its primary focus is on efficient service delivery to the litigants, lawyers and other stakeholders. It aims to use free and open source solutions (FOSS) and provides for setting up a Judicial Knowledge Management System (JKMS) to promote use of digital libraries. The focus areas are development of mobile applications, kiosks in court complexes for information dissemination and the integration of payment gateway for making deposits, payment of court fees, fines etc. The currently functional National Judicial Data Grid (NJDG) will be further improvised to facilitate more qualitative information for Courts, Government and Public under Phase II of the program.

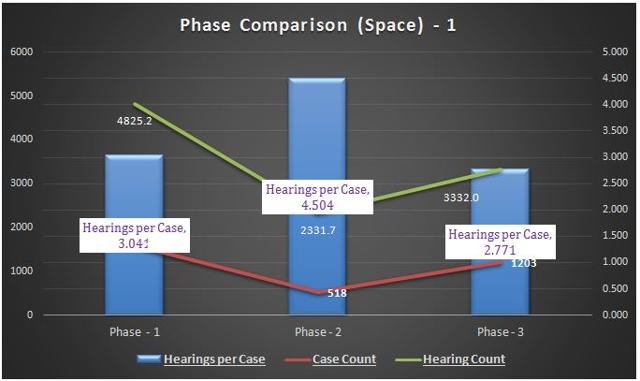

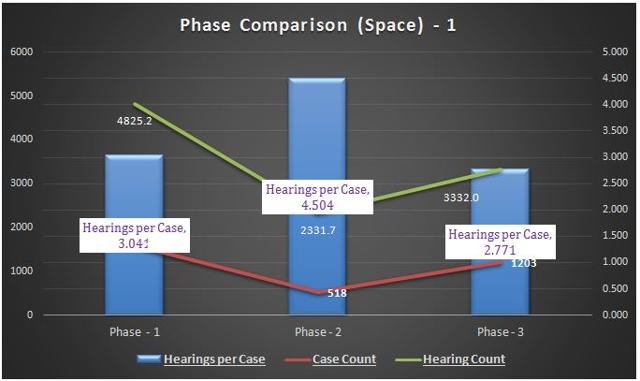

Hearings/case initially increased from 3.0 to 4.5 in the transition phase. Post transition the hearings/case reduced to 2.7 on an average. Based purely on anecdotal evidence gathered from lawyers and litigants in the court, this change can be attributed to a multitude of factors like lack of training for judges, lawyers and other stakeholders, behavioural resistance towards new systems as well as inadequate infrastructure to accommodate the shift from paper to paperless. Data also tells us that the average hearings per case have come down post the transition phase, effectively increasing the productivity of the court. This will in turn decrease average case age, an important parameter for measuring case pendency in the country. The increase in productivity can also be attributed to lesser human interaction, synchronisation among departments, effective communication between stakeholders, as well as better accessibility for the judges.

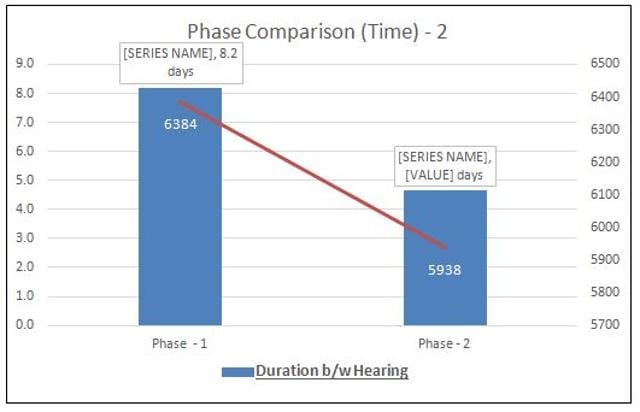

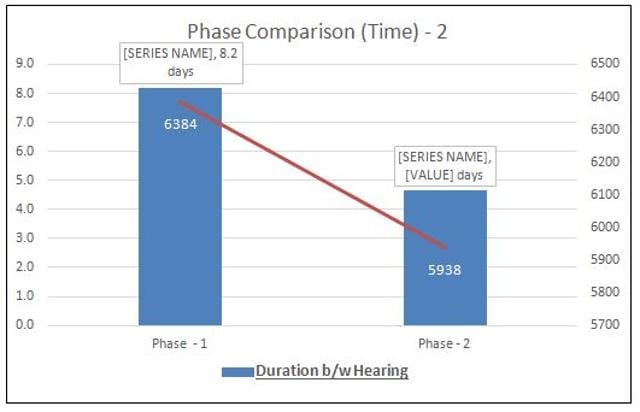

If we change the phases and compare data from 2015 (Phase 1) against that of post implementation of paperless court (Phase 2) we can see that the duration between hearings has almost reduced to half! This significantly brings down case age.

While one could argue that the timeframe of a year is not large enough to draw historic inferences, what cannot be missed is the fact that successful implementation of ICT interventions reduces average case age, a parameter directly responsible for increasing pendency in courts.

Teething is the beginning

Acclimatising to the digital way of work will probably be the lesser of the concerns that the Supreme Court will be facing in the long term. The court will have to begin with creating a digital library on the lines of the registry of the court for storing all digital documents. These would then be replicated at lower courts and finally interconnected such that they are accessible to the courts as well as the general public. Securing such databases would be of paramount importance as any breach would directly challenge the legitimacy of judgements. There would be a need to make such a connected system 'always-available' because delay in access would inevitably be delay in dispensing justice. The government will have to take a call as to whether it would allow such data to be hosted on the cloud that doesn't have geographical boundaries or will it invest in data centres specifically meant to store this data within our geographical boundaries. In the not so distant future, policies for incorporating artificial intelligence and machine learning based applications in administration of justice may also be needed.

With the introduction of the ICMIS in the Supreme Court, all eyes are on the current government to push for e-courts across the country. It is beyond doubt that technology will enable efficient justice delivery, but efficiency, should not be passed off as reform. Judicial reform in its true sense would be in ensuring a more accessible and equitable justice delivery system. To achieve this it is important that political will is backed by a long term nationally coherent reform strategy.

(Ranjeet Rane is the lead for digital policy at The Dialogue. Ahmed Pathan is a data analyst working with Daksh. Sahil Raveen (NLSUI, Bangalore) contributed research inputs for this article. Views expressed are personal.)

Catch all the Latest Tech News, Mobile News, Laptop News, Gaming news, Wearables News , How To News, also keep up with us on Whatsapp channel,Twitter, Facebook, Google News, and Instagram. For our latest videos, subscribe to our YouTube channel.