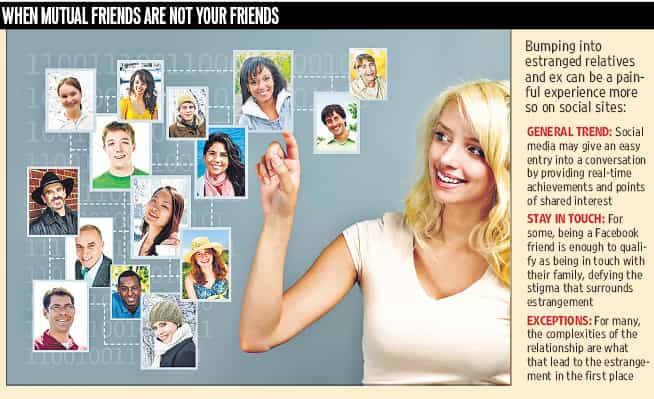

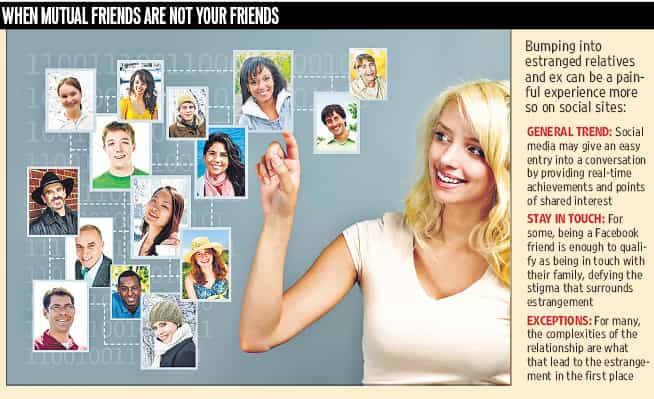

FB folly: When social sites don’t understand estrangement needs

Faux pas: Algorithms that make ‘friend’ suggestions don’t cater for complexities found in human relationships, especially families. When mutual friends are not your friends

My mother popped up on Facebook a few months ago as a "suggested friend". Her smile came up on the side of my screen, and I couldn't help but let my mouse gravitate to her name and linger over it.

With most people, if their mothers are already on Facebook then they're already "friends". But I became estranged from my parents half a decade ago, and hadn't exchanged words with my mother for over four years.

At a time when there's so much discussion about a "right to be forgotten" and methods to delete your digital life, I've done a lot to digitally forget my parents, and delete them from my digital life.

I'd rejected invitations to connect from their work colleagues and friends so that snippets of their life wouldn't flash incidentally into mine and tempt me to linger.

Yet within seconds of my mother's profile flashing up on the screen, I found myself wading through my parents' most recent social occasions. It was exactly as I feared: they appeared absolutely fine. Dad was wallpapering in socks and sandals in a house in Coffs Bay, smiling. Mum had commented underneath: "my hero wallpapering". Next they were sat on a grassy hill, holding up glasses of white wine, beaming in the sun. That particular album was labelled London 2012. Image by image, I saw them posing outside the monuments in our capital and my current home.

I know - you're expecting the film script trajectory: the images lead me to end the estrangement, the family is reconciled, and in a faraway office Mark Zuckerberg smiles and rings a bell as another angel gets its wings.

Sorry. Not so. Instead, my reaction was to think: how could they just turn up and smile in a city where they knew that their daughter is living, breathing and working? I slammed my computer shut. I knew too much.

It was the resolute happiness that was shocking, and my mum's profile picture continued to nag me all week. Then it hit me: if she ever saw my profile then I'd be smiling back. My page is a savvy edit of my best happenings - picnics, festivals, and holidays in Barcelona. There are no posts about the sleepless nights and awkward moments where I struggle to explain to people why I don't "have a family". I didn't post a screenshot of the letters I sent them, trying to discuss our feud rationally and asking the questions that were natural to ask.

Perhaps I've been quietly coerced into thinking that positivity is the currency in which our online profiles trade, and so I instinctively stay away from the sombre. This illustrates the dichotomy inherent to social networking: the digital world allows for "togetherness" in which we "share our lives" with people around the world - yet conversely it can distance us from friends' fully dimensional experiences of life.

This permanent state of online happiness, as projected by a profile, can be mentally destabilising for those with discordant relationships. Dr Joshua Coleman, a psychologist based in San Francisco who is a specialist in estrangement, and author of When Parents Hurt, observes: "We have never in our history been as accessible to our family and friends. Social media, on the one hand, allows us to connect quickly to those we love. On the other, it allows those that we love — or once loved — enormous power to reach us and hurt us from almost anywhere in the world."

He explains one easy way of doing that: "announcing critical events such as weddings, while not letting the family member know directly, and tormenting the person in isolation by posting photographs of events where they were absent."

It seems this issue is amplified by the prolific use of images. For me, the photographs I gazed at alluded to my parents' satisfaction in isolation, yet at the same time allowed me a vicarious experience of that happiness. For a few minutes I was really with them in London, experiencing their wonder and excitement - only to remember soon after that I wasn't really welcome, not with my questions.

This could be an issue with privacy, as my mother's photographs were all accessible without our being online friends. The question remains: should social networking sites step up and offer to help those who don't wish to be reminded of their estrangement? Facebook claims to have the advantage of being able to block users, whereas you wouldn't be able to block a person if you encountered them on the street.

For some, being a Facebook friend is enough to qualify as being in touch with their family, defying the stigma that surrounds estrangement. For many, the complexities of the relationship are what lead to the estrangement in the first place. Coleman says: "It's useful to remember the positive aspects to a person when thinking about reconciling with a family member. This will give us a better chance of seeing the process through. Social media may give an easy entry into a conversation by providing real-time achievements and points of shared interest." If social media can facilitate such positivity, albeit about career or personal life, it could be seen as a useful tool in developing the mindset needed for the reconciliation process itself.

It's a tall order. I work in a world that demands an online presence. I can't delete my digital life. Except the computer that has mediated the meeting has no concept of life or its complications — only tables in a database that have found a match.

Catch all the Latest Tech News, Mobile News, Laptop News, Gaming news, Wearables News , How To News, also keep up with us on Whatsapp channel,Twitter, Facebook, Google News, and Instagram. For our latest videos, subscribe to our YouTube channel.