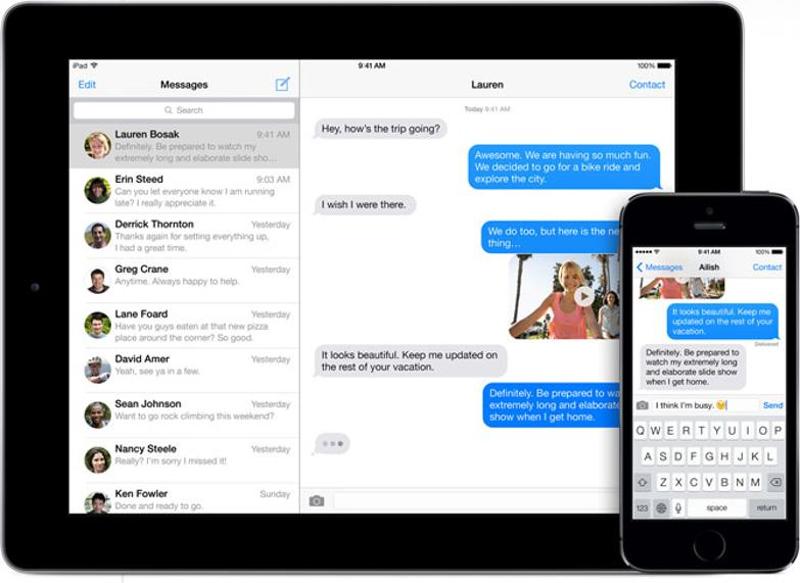

Apple refuses governments a peek into our messages

With governments threatening crackdowns on encrypted communications after the jihadi-inspired attacks in San Bernardino, California, and Paris, Apple on Monday pushed back hard, arguing that lawmakers who talk about gaining court-ordered access to iPhone communications do not understand the technology.

Governments threated crackdowns on encrypted communications after the jihadi-inspired attacks in San Bernardino, California and Paris. On Monday, Apple pushed back hard, arguing that lawmakers who talk about gaining court-ordered access to iPhone communications do not understand the technology.

"The best minds in the world cannot rewrite the laws of mathematics," the company told the British Parliament, submitting formal comments on a proposed law that would require the company to supply a way to break into the iMessages and FaceTime conversations of iPhone users.

"We believe it would be wrong to weaken security for hundreds of millions of law-abiding customers so that it will also be weaker for the very few who pose a threat," Apple wrote.

Apple's statement came as questions about encryption — considered a wonky component of cybersecurity just a few months ago — has become a central issue in the U.S. presidential campaign.

Twice in the past three weeks, Hillary Clinton, the leading contender for the Democratic nomination, according to polls, has urged Silicon Valley companies to work with Washington to find a way out of their standoff over encrypted communications.

Republican candidates have almost all called for giving intelligence and law enforcement agencies the kind of access to text messages and data stored on cell phones that they have long enjoyed with telecommunications providers, like AT&T and Verizon. Congress is calling for hearings, and there is talk of legislation, though it seems unlikely to include the kind of demands for access that Britain's prime minister, David Cameron, advocates.

The arguments made by Apple are not new, but the political context is. In the aftermath of the two most recent terrorist attacks, the political pendulum has swung away from protecting privacy — the direction Europe was moving after Edward J. Snowden, the former intelligence contractor, leaked classified documents on government surveillance — and more toward law enforcement.

The technology companies argue that although the political winds may be changing, the technological challenge has not: To create an opening for government investigators is to also create a vulnerability that Chinese, Iranian, Russian or North Korean hackers could exploit.

Clinton rejected that argument recently, arguing that if the companies wanted to put their best minds to the problem, they would solve it.

But in the British filing, and in an interview on 60 Minutes on Sunday, Apple's chief executive, Tim Cook, argued that politicians calling for such access do not understand the damage they would cause.

So far, Cook still has a partial ally in President Barack Obama. The White House determined in October that, despite a recommendation from the FBI to put forward legislation requiring access to encrypted communications, it would not seek legal changes. That rankled the FBI director, James B. Comey, who has long warned about the "going dark" problem, and offered up evidence a week ago that an attack in Texas this year had been plotted over encrypted text messages, which he said investigators still could not crack.

Apple pushed back on Comey's arguments in its submission to the British government. "Some would portray this as an all-or-nothing proposition for law enforcement," it wrote. "Nothing could be further from the truth. Law enforcement today has access to more data — data which they can use to prevent terrorist attacks, solve crimes and help bring perpetrators to justice — than ever before in the history of our world."

That data, many experts say, includes phone "metadata" about who is calling whom, GPS coordinates for individuals, and access to unencrypted data stored on so-called cloud services. But the arguments in Britain and the United States have focused largely on systems designed by Apple and its competitors, including Google and Microsoft, that automatically encrypt data exchanges, and put the keys to those communications into the hands of the users, not the companies.

Apple contended that if Britain went ahead with its legal changes, the company, and its competitors, may find themselves violating U.S. laws to comply with British law — or vice versa. "This would immobilize substantial portions of the tech sector and spark serious international conflicts," it argued.

Catch all the Latest Tech News, Mobile News, Laptop News, Gaming news, Wearables News , How To News, also keep up with us on Whatsapp channel,Twitter, Facebook, Google News, and Instagram. For our latest videos, subscribe to our YouTube channel.