Climate Change: Why Are Some Climate Models Running Red Hot? Scientists Have an Answer

Climate Change: Experts emphasize the importance of not making climate projections look worse than they already are.

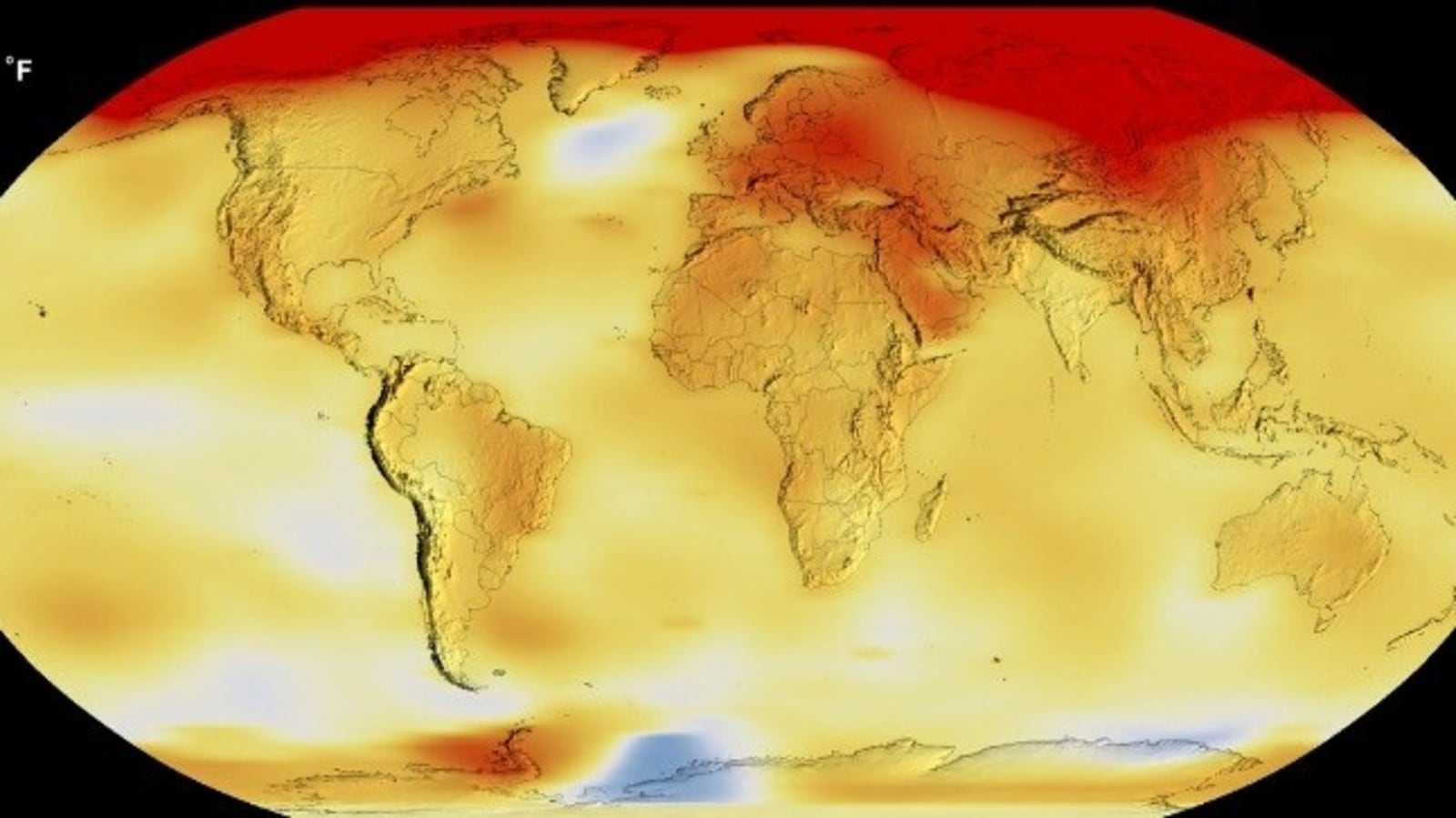

Something funny happened when, three years ago, climate scientists began reporting results from their latest generation of Earth models. A concerning number of them showed accelerated heating.

These “hot models” quickly raised alarm. It's a puzzle that's now well on its way to being solved, according to a commentary published today in the journal Nature by five leading scientists. Advances that include better understanding of the physics of clouds had the unanticipated effect of raising overall temperatures faster in some models.

With the effects of climate change visible virtually every week, governments, companies, investors and communities are all hungry for high-quality information about what's coming next. How to treat the hot models is a key part of that, and the authors highlight just how to tap what's useful about them.

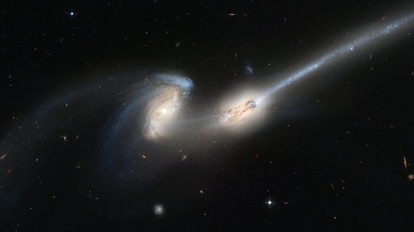

Climate models are the complex research workhorses that for decades have correctly, for the most part, projected how temperatures would rise from continued greenhouse gas pollution—“the best window on the future world that climate scientists have,” said Richard Betts, head of climate impacts research at the U.K. Met Office, who was not involved in the new article. They are driven by the physics of how carbon dioxide and other gases absorb heat, how much light ice caps reflect to space and myriad other phenomena that generations of scientists have observed in the real world.

Where physics can't fully capture natural processes, modelers approximate how the world behaves—and that's where the headache in the latest model updates probably came about. These models, which formed the backbone of the latest United Nations climate assessment that began publishing in August, included more sophisticated looks at the science of ice, water and clouds that appear to have pushed higher some models' answers to the central question of how much CO₂ causes how much warming.

The UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change took the hot models problem seriously in its latest round of reports and ended what scientists refer to as “model democracy,” or treating every research model as equal to all the others. The hot models received less emphasis, and the IPCC added on another layer of analysis after that.

Despite the IPCC's recent work, the Nature authors worry that in the years ahead, it's no one's job to encourage best practices that prevent the hot models from turning up in research where they might indicate more warming than is already on its way. They emphasize that what's expected from climate change is bad enough, and as governments and companies increasingly look harder at what climate projections mean for them specifically, the most precise science is more critical than ever.

Overall, the newest models' output “is a lot of the data that's then going to be used by companies, by local governments, by local policymakers for adaptation, planning purposes,” said Zeke Hausfather, an author and climate research lead at Stripe. “The last thing we want to do is tell everyone we're going to have a bunch more warming than is likely.”

The first of the largely technical recommendations in the Nature article regarding the hot models is useful beyond the pages of scientific journals. It's to start thinking about climate change more in terms of warming levels than what year we may hit them. When the rate of warming, which is the core issue with the hot models, isn't a key factor in new and especially risk-related research, Betts said, the models are still useful to “provide the most complete information on potential impacts and adaptation needs.”

Climate change is inherently full of surprises, which makes timelines—what will happen by 2030, by 2050, by 2100—less reliable than understanding what each increasingly undesirable temperature increase means—1.5°C, 2°C, 3°C.

“The takeaway is that, well, what's the optimal best time to reach 2° warming? It's never, right? Let's not do that,” said Kate Marvel, an article co-author and a research scientist at Columbia University and the NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies.

Catch all the Latest Tech News, Mobile News, Laptop News, Gaming news, Wearables News , How To News, also keep up with us on Whatsapp channel,Twitter, Facebook, Google News, and Instagram. For our latest videos, subscribe to our YouTube channel.